The History of Tyrian Purple

True Tyrian purple is a marine-organic dye made from Mediterranean murex snails, first industrialized by the Phoenicians and later reserved for emperors, bishops, and imperial courts until the Byzantine empire fell in 1453. In the last two decades, Tunisian artisan Mohamed Ghassen Nouira has famously revived the full snail‑based process, producing true murex purple again for textiles and artworks.

Tyrian purple is produced from the hypobranchial glands of several murex species, especially Bolinus brandaris, Hexaplex trunculus, and Stramonita haemastoma. Ancient sources and modern reconstructions show that thousands of snails were broken, the glands extracted, and the secretion fermented and exposed to light and air until it oxidized into a stable purple dye.

Archaeological and textual evidence place the first manufacture of Tyrian purple with Phoenician centers such as Tyre and Sidon in the Late Bronze Age, roughly 16th–13th century BCE. The very name “Phoenicia” is commonly interpreted as “land of purple,” reflecting how closely this dye was tied to their maritime trade and identity.

Because it required vast labor and huge quantities of snails, Tyrian purple was more valuable than silver and in some cases compared to or beyond gold by weight. As a result, it became a legal and religious marker of rank.

In classical Greece and especially Rome, purple-bordered magistrates’ togas and the full purple toga picta or toga triumphalis signaled supreme political and military authority. Roman emperors eventually restricted Tyrian purple by law; under some rulers, wearing an all‑purple cloak without permission could be treated as treason.

In the Hebrew Bible tradition, purple from the sea appears in descriptions of tabernacle and temple textiles; 2 Chronicles describes King Solomon employing a Tyrian craftsman skilled in purple for the First Temple’s veil.

Very little ancient purple cloth survives, but the dye appears across regalia, liturgy, and art that people still see today.

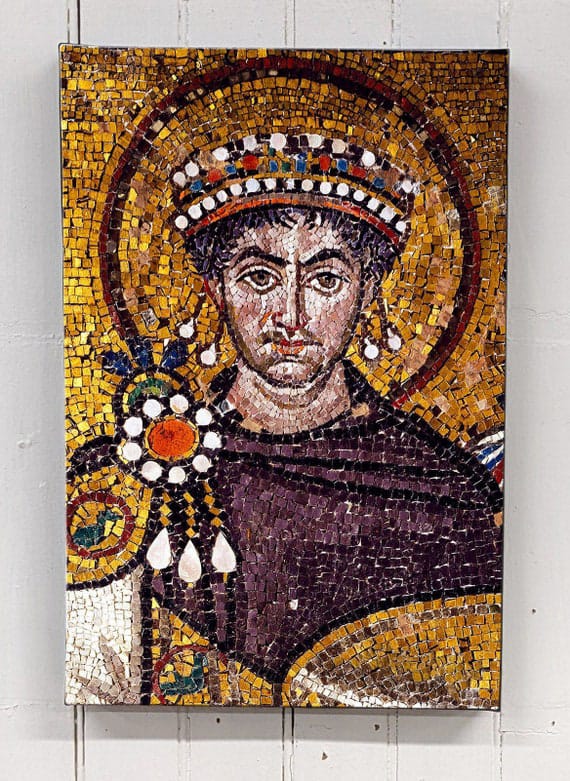

Imperial and royal regalia: Roman and Byzantine emperors used Tyrian purple for cloaks and linings, while the phrase “born in the purple” refers to Byzantine princes born in purple‑paneled imperial chambers. Gold crowns and scepters were often paired with purple mantles as a unified symbol of sacral kingship.

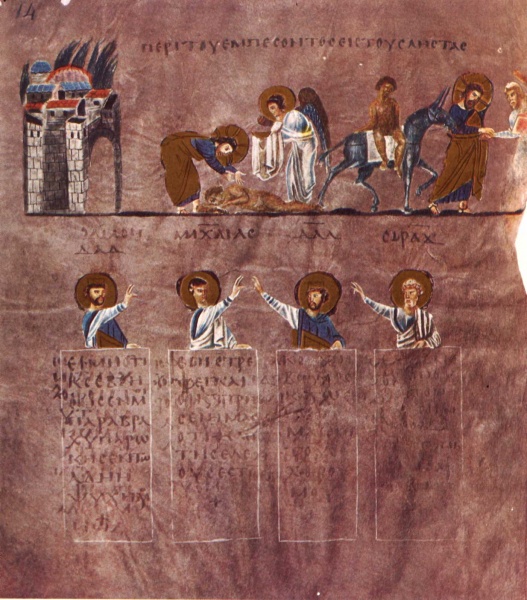

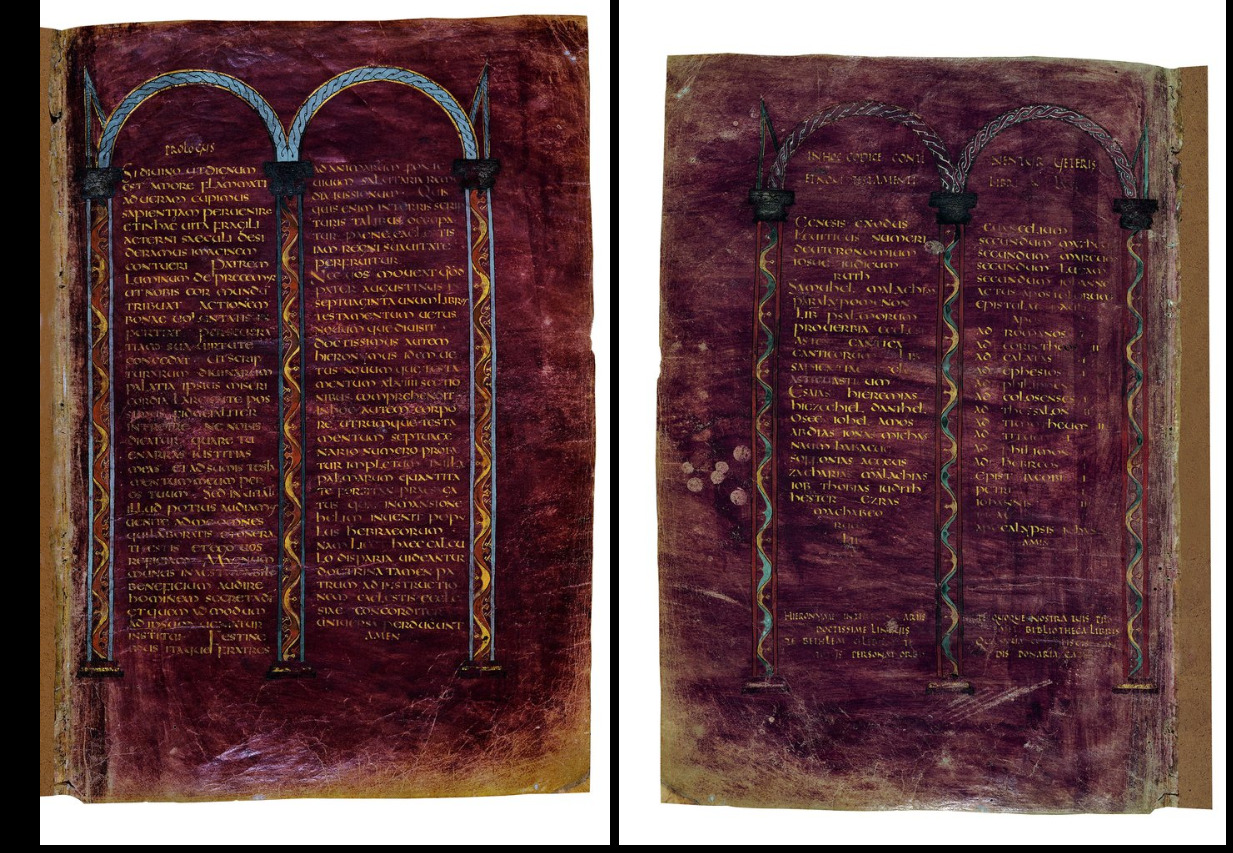

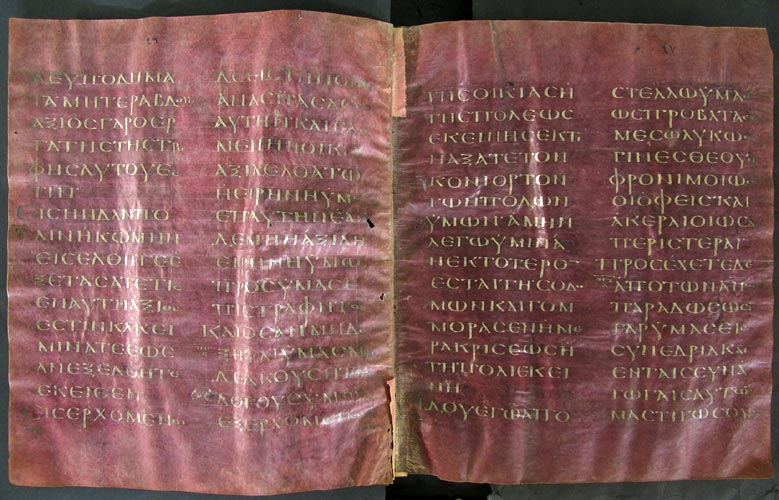

Purple codices and manuscripts: Late antique and early medieval “purple codices” were written on parchment dyed purple with murex‑based dyes, then inscribed with silver and gold ink; surviving examples include several 6th‑century Gospel books in museums and church treasuries.

Panel paintings and illuminations: Technical studies have detected bromine—a marker of murex dye—in certain medieval and early Renaissance artworks. In 2024, excavations at a Roman bathhouse near Carlisle in the U.K. uncovered a concentrated clump of Tyrian purple pigment, confirming its use far from the Mediterranean.

After the Phoenician city‑states, production continued under Hellenistic kingdoms, then Rome, and finally Byzantium, which guarded the dye as an imperial monopoly. With the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the last state system that legally controlled large‑scale Tyrian purple craft collapsed, and traditional knowledge faded.

By the early modern period, most “royal purple” fabrics used cheaper substitutes, and murex‑based purple became a historical curiosity rather than an active industry.

In the 19th century, chemists isolated the main colorant, 6,6′‑dibromoindigo, proving Tyrian purple is a distinct brominated indigoid dye. This set the stage for modern revivals.

Tunisian artisan Mohamed Ghassen Nouira, fascinated by Carthaginian history, encountered murex shells on the beaches near Carthage and spent over a decade experimentally rediscovering how to process them into purple dye.

Working largely by hand in his garden workshop, he breaks shells, extracts the glands, and manages controlled oxidation to produce minute quantities of true snail‑based purple, which he applies to threads, textiles, and demonstration pieces that echo ancient prestige uses.

Nouira explicitly frames his craft as the rebirth of a Phoenician–Carthaginian art, and he has expressed hopes of seeing his purples in Tunisian museums and of passing the technique to future apprentices.

Today, authentic murex Tyrian purple remains extremely scarce and expensive, used mainly in niche fine‑art pigments, experimental reconstructions, and a handful of luxury textiles—while its cultural power endures in the imagery of crowns, scepters, and the phrase “born in the purple.”